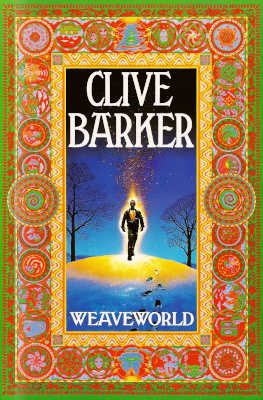

Weaveworld by Clive Barker

Full disclosure: I didn’t actually read Weaveworld by Clive Barker. I listened to it in the form of an audiobook.

What can you expect from the writer who brought the Hellraiser serie and other such horrors into the world?

Not horror. That’s for sure.

Weaveworld falls firmly into the category of magical realism, with a few elements of horror. It’s set in the ordinary world, except there’s a race of magical people known as the Seerkind, who possess all kinds of abilities and whimsical attributes.

Most of the action is set in the 1990s Liverpool and on the Wirral, and as I am a native of such parts, it’s fun to read about places I know and love. The action at Thurstaston is particularly satisfying.

So, with the book being set in my neck of the woods, how come I haven’t seen any of these magical people and their raptures?

The answer is that the people, their houses, orchards, gardens, lakes, and pavilions have been woven into a carpet and hidden away for a century from the mysterious Scourge which is bent on the destruction of all Seerkind.

The story follows the adventures of Cal, a young man from Woolton who has an unexpected encounter with the carpet, and Susanna, the Granddaughter of the mysterious weave’s last guardian.

There is a variety of villains all with their own aims and unique characteristics, fairly well written and suitably weird for a master of horror. Some of them are particularly horrific, grotesque, and disturbing.

Weaveworld is long and took almost a month to digest. A part of this is probably because it takes more time to listen to the spoken word than it does to read actual words on a page.

It’s also long because it’s a long book full of constant twists, unexpected turns, and stunning revelations.

I liked Weaveworld, but the book is showing its age. It is very much a product of the 1990s, and the language reflects that.

Overall, it’s a great adventure story, and ranks up along Gaiman in the sphere of the genre.

One additional point is that the book was recorded in the 1990s. It’s very well done, but it’s obvious that digital editing wasn’t a thing and that the narrator was not reading from a screen.

Occasionally, the listener can hear pages turning, and very occasionally, there’s what might be background traffic.

It’s charming to experience the relics of a pre-digital age through a book in which magic exists but mobile phones do not.